The Pabenham-Clifford Hours

Books of Hours, often personalised for individual use, were essential to the devotional practices of both the clergy and lay people who counted them among their most cherished possessions. This Book of Hours was specially designed for a couple, probably to commemorate their marriage.

The couple for whom the manuscript was made, John de Pabenham (d. 1331) and his second wife, Joan Clifford, who were married c. 1315, are depicted several times in the volume. In two full-page miniatures painted on burnished gold grounds, the pair are shown kneeling in supplication. Their arms are emblazoned on their garments and additional heraldry in the margins reflects their familial and feudal allegiances. This profusion of arms and the exuberant decoration reveal the couple’s social ambitions. As members of the gentry, the patrons aspired to own the type of richly illuminated manuscript normally associated with aristocratic patronage. Illuminated initials enclosing human heads and margins filled with playful paintings of imaginary beasts and hybrids enhance the decorative programme. The fanciful creatures are shown alongside depictions of actual birds and animals that reflect a growing interest in the natural world typical of early 14th-century English illuminators.

Learn more about the manuscript by exploring the sections below or selecting folios on the right. Discover further details by choosing any of the folios with the hotspot symbol ![]() .

.

The manuscript preserves no evidence of its place of production or the artists’ origins and place of work. Yet, two of the volumes in a group of stylistically related manuscripts to which it belongs point to the Midlands. The Vaux Psalter (London, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 233) includes in its Calendar saints venerated in the Midlands, and the Tickhill Psalter (New York, Public Library, MS Spencer 26) was made at Worksop Priory in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands. The repetition of motifs across these different manuscripts shows that the illuminators made use of shared patterns and models. Two of the bas-de-page motifs found in this Book of Hours are also seen in the Vaux Psalter, and some initials filled with human heads are identical to those in another related volume: the Welles Apocalypse (London, BL, MS Royal 15.D.II), which was probably illuminated by some of the same artists. It is likely that they were itinerant professionals who travelled across the Midlands and the East of England, working on commissions in various locations and collaborating with a range of specialist craftsmen.

This manuscript was made for John de Pabenham (d. 1331) and his second wife, Joan Clifford, probably to mark their marriage c. 1315. While the manuscript was in the collection of Sir Andrew Fountaine (1676-1753) of Narford Hall, Norfolk, two leaves were removed from it by Sir John Fenn (fols. 37 and 55). The leaves were purchased at his sale (Puttick’s, London, 16-18 July 1866, lot 865) by Samuel Sandars (1837-1894), who gave them to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1892. William Morris (1834-1896) bought the ‘parent’ manuscript at the Fountaine Sale (Christie’s, London, 6 July 1894, lot 143). Following negotiations with the Fitzwilliam, in 1895 the two leaves were reunited with the volume, which came to the Museum after Morris’ death in 1896.

The manuscript contains the texts standard for Books of Hours by the early 14th century, but it also includes two texts that would become common later in the century, the Hours of the Trinity and of the Holy Spirit. It lacks the Calendar and most of the Litany, which could have helped establish where the volume was made.

Full-page miniatures introduce the Hours of the Virgin and the Hours of the Trinity. A similar frontispiece, now lost, probably would have introduced the Hours of the Holy Spirit. In addition, three large historiated initials with full borders mark the main text divisions: one for the Hours of the Virgin, one for the Hours of the Trinity, and another for the Penitential Psalms. Similar initials almost certainly would have adorned the leaves now missing at the beginning of the Hours of the Holy Spirit (after fol. 42), the Gradual Psalms (after fol. 64), and the Office of the Dead (after fol. 66).

The minor text divisions are marked by initials of three main types: medium-sized initials enclosing human heads on gold grounds, initials of a similar size with stylised foliate patterns, geometric, knotwork and interlace motifs, also on gold grounds, and smaller gold initials in alternate pink and blue frames highlighted in white. The lower borders (bas-de-page) are decorated with whimsical motifs, including imaginary creatures, animals and birds.

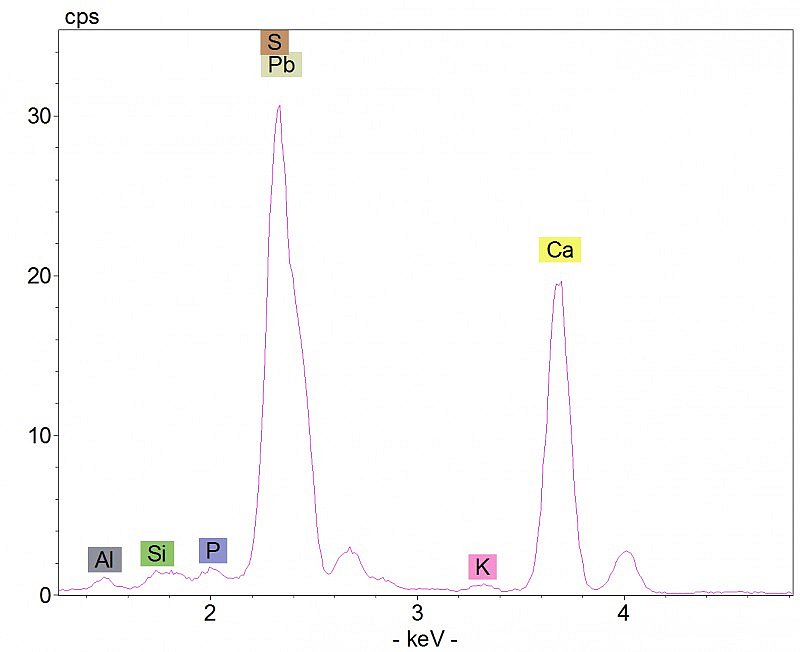

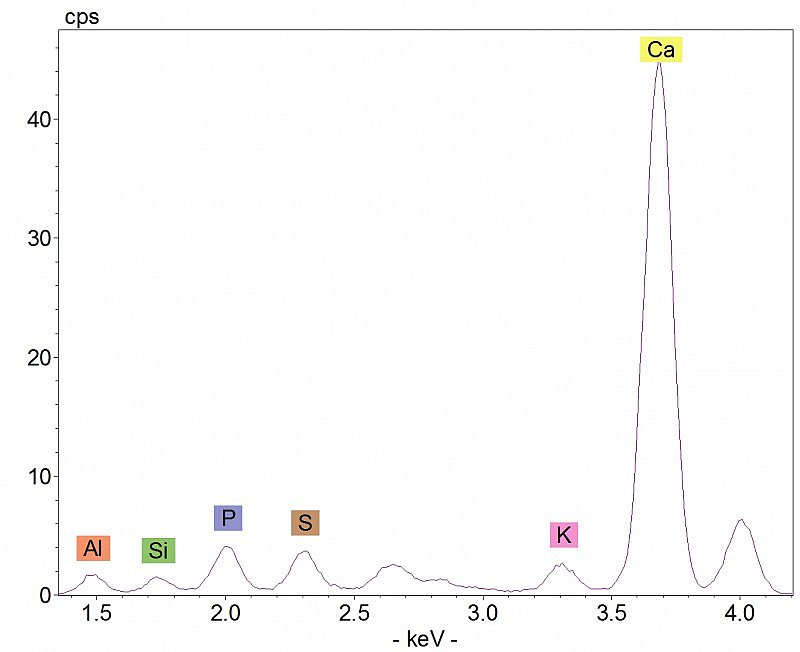

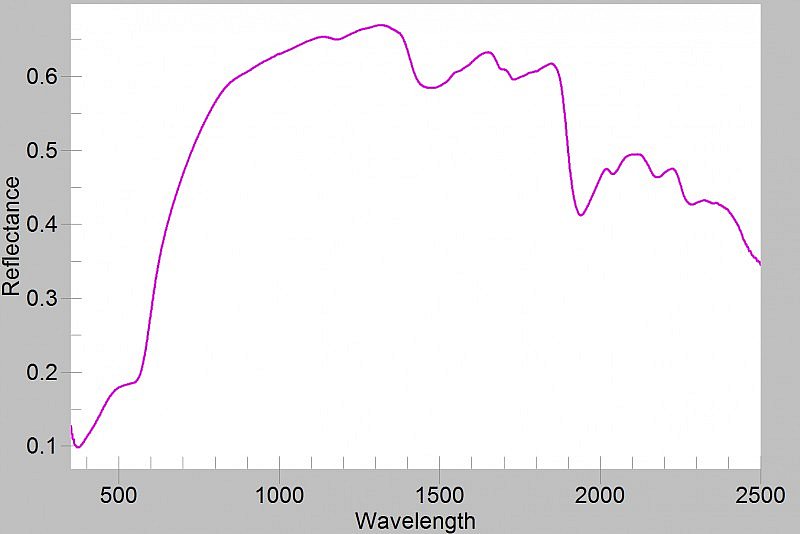

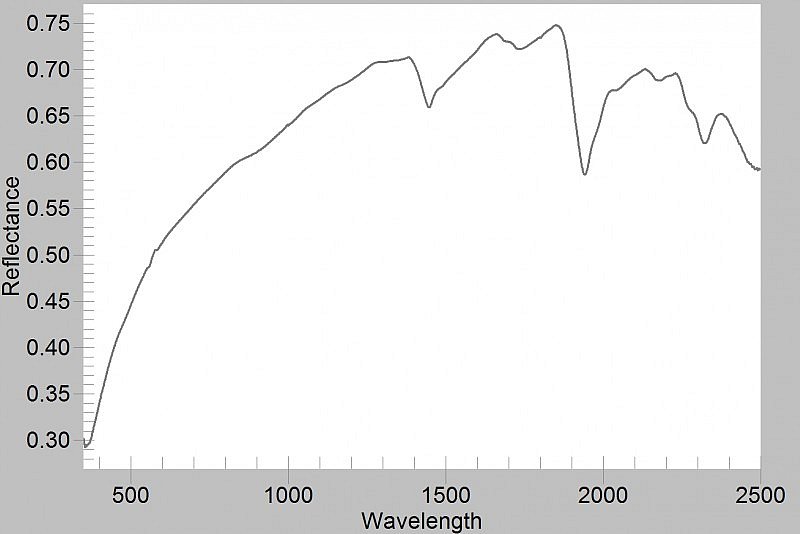

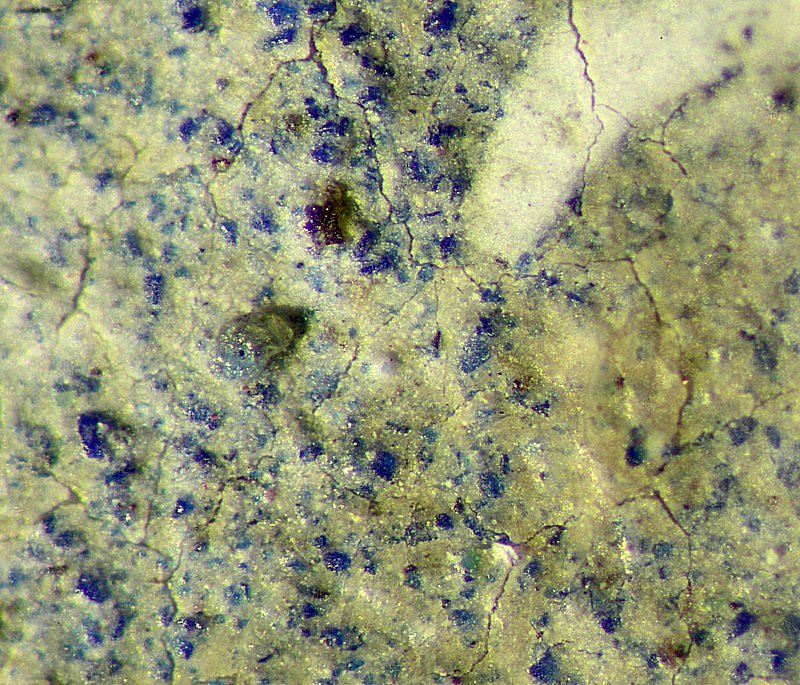

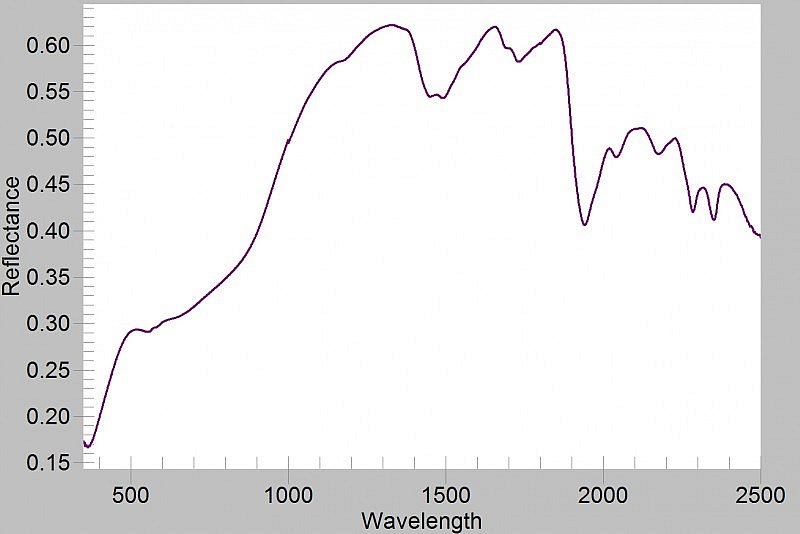

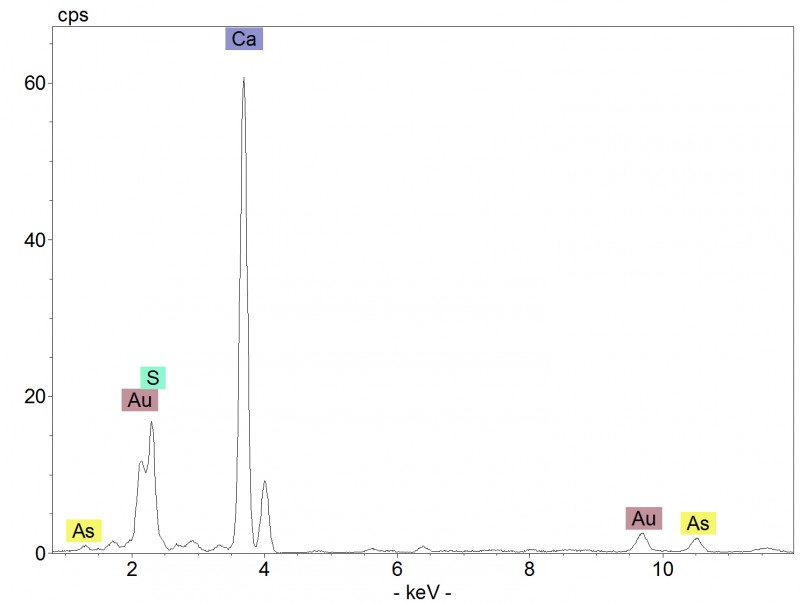

Carbon black, lead white (usually mixed with gypsum), azurite, verdigris, red lead and vermilion were used in every illumination. Red dyes, likely extracted from insects, provided pink hues when mixed with chalk or lead white and gypsum. Brown hues were obtained by mixing organic dyes and lead white, with the occasional addition of gypsum and copper-based pigments. Yellow, generally mosaic gold, was used sparingly and was reserved for details. In the areas of the pictorial decoration that were analysed, arsenic sulphide was identified as the yellow hue employed in only two instances. Flesh tones were modelled on a lead white and gypsum base and shaded with delicate light brown washes of an organic colourant. Facial features were outlined in carbon black.

Gold leaf was used extensively in the miniatures’ backgrounds, the patrons’ clothing and coats of arms, and in small initials. Silver is also present in the coats of arms and clothing, where it has tarnished and shows abundant losses.

Some differences were observed on fol. 3r, suggesting that the historiated initial on this page was painted by a different artist.

Underdrawing is present on several folios, especially in the draperies. It is visible in the infrared images and also beneath the semi-transparent pink areas. Differences were observed in the way that draperies were modelled and the gold leaf was treated on some folios.

.jpg)

Annunciation with John de Pabenham and Joan Clifford kneeling in the lower margin (Hours of the Virgin)

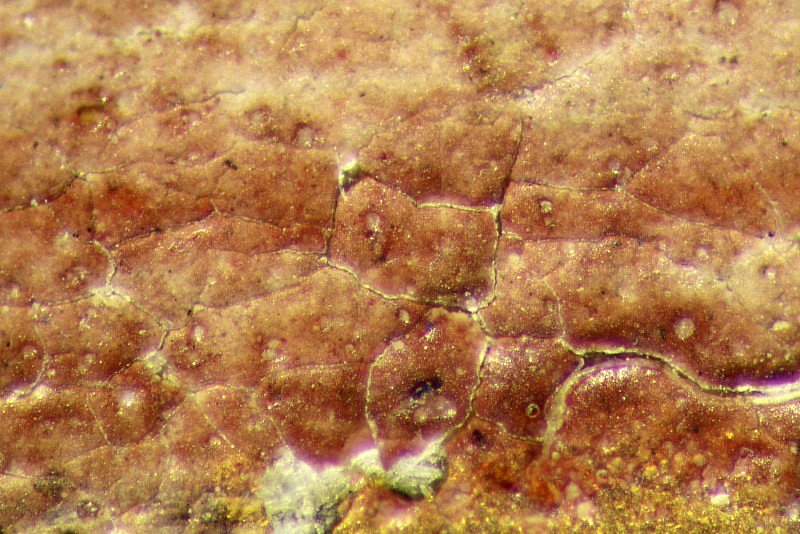

Underdrawing for the draperies is visible in the infrared image, as well as through the semi-transparent paint used in the Virgin’s pink mantle. This garment was painted with a mixture of an insect-based red dye, lead white and gypsum (hotspot 1), while Gabriel’s dark pink tunic contains a red dye mixed with chalk (hotspot 2). Gabriel’s blue-grey wings contain azurite blue and small quantities of an organic red, as can be seen under magnification (hotspot 4). The tooled gold leaf in the background was additionally decorated by painting a pattern of spirals with an arsenic sulphide yellow pigment, likely orpiment (hotspot 5).