Typology

The New Testament is hidden in the Old: the Old is made clear by the New.

St Augustine, City of God, XVI, 26

It was not only the book of Psalms that was thought to prophecy the events of the New Testament. As a way of validating itself over Judaism, early Christianity interpreted much of the Old Testament as a prefiguration of the New.

Addressing the Pharisees, a strict and powerful Jewish sect, Jesus himself says at Matthew 12, 40:

For as Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale’s belly; so shall the son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.

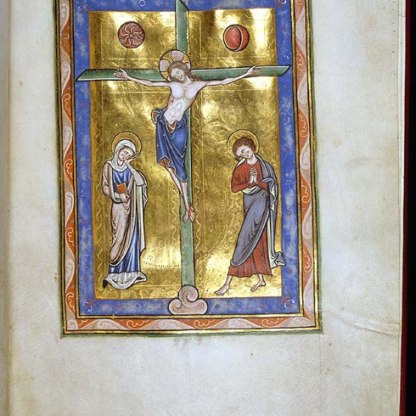

He uses an example from the Jewish past to explain the Christian future: his own death and Resurrection. Jonas – or Jonah as we know him today – is a ‘type’ of Christ. This method of iblical interpretation is called typology and lies behind much medieval religious art. Where an Old Testament scene is shown in a church window, on an altarpiece or in a book, it is often to be interpreted as foreshadowing an event in the New Testament.

King David is one of the most important types of Christ. As the son of Jesse, he is cited as a direct ancestor of Jesus. The Old Testament Book of Isaiah prophesies, at 11, 1–2, that

... there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots: And the spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him ...

The Tree of Jesse, showing Christ's mortal ancestry, was often depicted in illuminated psalters in the middle ages. On the left is a leaf from a thirteenth-century psalter in the Fitzwilliam [MS.330 (ii)], showing a tree growing from the loins of a sleeping Jesse. Within the branches are Christ's forebears, with Jesus himself at the top.

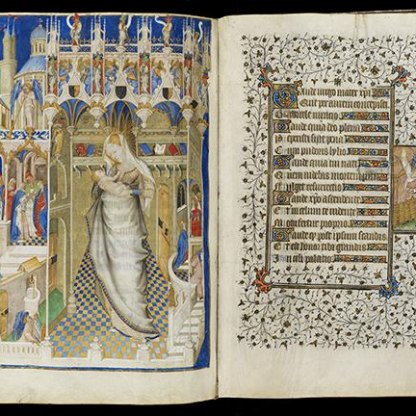

The Speculum Humanae Salvationis ('The Mirror of Human Salvation'), written c. 1324, was one of the most important medieval typological texts. For every New Testament subject dealt with, the author of this book offers several prototypes from the Old Testament or from history.

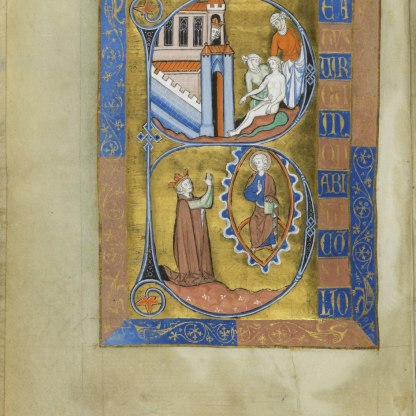

So, in a late fourteenth-century Italian Speculum in the Fitzwilliam Library [MS.23], a representation of Christ tempted by the Devil [folio 14v] is accompanied by three stories in which Sin is defeated.

The first story is the most obscure, and comes from one of the Apocryphal books of the Old Testament. It tells how the hero Daniel defeated a dragon and destroyed the pagan idol Bel [folio 14v]. Both Bel and the Dragon were held to represent gluttony, explains the text, so this story prefigures Christ’s conquering the temptation of food whilst in the wilderness. Daniel is a type of Christ.

The next story is the more familiar one of David killing the giant Goliath. In the miniature the young king is shown about to cut off his enemy’s head, having felled him with a sling-stone [folio 15r]. Since Goliath was boastful and proud of his great strength, we are told, this specifically prefigures Christ’s conquering the temptation of pride.

The third Old Testament story involves David again [folio 15r]. This time he fights a lion and a bear, wild animals that had attacked his flock while he was a shepherd. This foreshadows Christ’s conquering of avarice.

Typological thinking was most widespread in the middle ages, but it continued into the Renaissance and beyond. Between 1625 and 1627 the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens designed a set of tapestries for the Infanta Isabella, daughter of the king of Spain, in some of which he used traditional typological images.

Some of Rubens' sketches for these tapestries survive in the Fitzwilliam, including 'The meeting of Abraham and Melchisedek' [231]. In this story from the Book of Genesis, the Old Testament patriarch Abraham, having liberated his nephew Lot from his enemies, is welcomed in Jerusalem by Melchizedek, the city’s king and high priest. Melchizedek offers Abraham bread and wine, and this feast of thanksgiving is seen as a prefiguration of the Last Supper, and by extension the Eucharist – the Christian sacrament in which celebrants eat bread and drink wine to remind them of Christ's sacrifice.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…