Terminus

It is clear from a description by the Roman poet Ovid, that Terminus could adopt different forms:

When the night has passed, see to it that the god who marks the boundaries of the tilled lands receives his wonted honour. O Terminus, whether thou art a stone or a stump buried in the field, thou too hast been deified from days of yore ...

The god's image here, with his youthful face, unkempt beard and wild hair, seems to be either Erasmus' or Metsys’ invention. But although the specific facial features are unique to this medal, the sculptural form of a head and shoulders on top of a pillar derives from ancient Greece.

From about the sixth century BCE, Greek sculptors produced herms – heads of the god Hermes carved into the top of a pillar, usually with an erect phallus halfway down. These sculptures were generally located out of doors and, as well as marking boundaries, were found in gymnasia and as wayside shrines.

By the fifth century, the features of other gods, such as Dionysos, Ares, Artemis and Aphrodite, appeared on the tops of pillar shafts. Public figures were also portrayed as heads on the top of columns, and this sculptural form continued to be popular in the Roman republic and empire. A coin of the Emperor Augustus in the Fitzwilliam [CM.638–1936] shows a herm of his adoptive father, Julius Caesar.

Figures specifically representing Terminus were called terms, although examples that can be identified specifically as Terminus are rare.

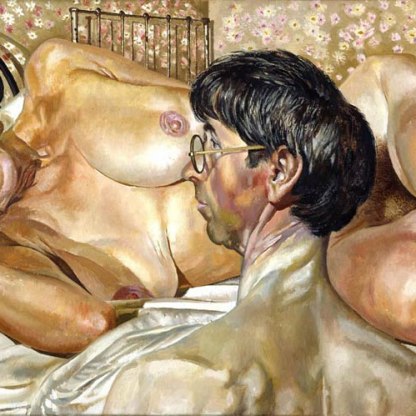

In Salvator Rosa’s seventeenthcentury painting L’Umana Fragilità, in the Fitzwilliam, detail [PD.53-1958], Terminus appears as a death symbol, a grizzled old face carved on top of a pillar, crowned with cypress.

The pillar with a head became popular as an architectural decoration in the Renaissance. Variations upon this theme, in which a male torso emerges from a pillar, can be seen in the interior of the dome in the entrance hall of the Fitzwilliam, left.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…