Cows and Bulls

As providers of meat and milk, as beasts of burden and agriculture, as metaphors of power and stability, and as objects of worship and sacrifice, the cow and the bull have been recorded by humans in their art since the earliest times. One of the oldest pieces of figurative art in the Fitzwilliam dates from c. 12,000 BCE: on a piece of stone from the Dordogne in France, the head of a bison has been etched, perhaps to ensure, by magic, success in the hunt.

In Egypt the bull had several meanings. The title ‘mighty bull’ or ‘bull of Horus’ was bestowed upon several pharaohs and the animals were seen as embodiments of strength and masculinity. The bull-god Apis was seen as the incarnation of the creator god Ptah, and worshipped at Memphis.

In the West, the very origins of Europe were explained in a Greek myth involving a bull. Zeus, the king of the gods, had fallen in love with the mortal princess, Europa, from the Phoenician city of Tyre, in modern Lebanon. To win her he turned himself into a magnificent bull and carried her across the ocean to the distant continent that would bear her name. The story is depicted, above, on a maiolica plate in the Fitzwilliam, dated 1524 [C.80-1927], and, below, [M.3–1968] in a small eighteenth-century bronze by the Italian sculptor Giovanni Battista Foggini.

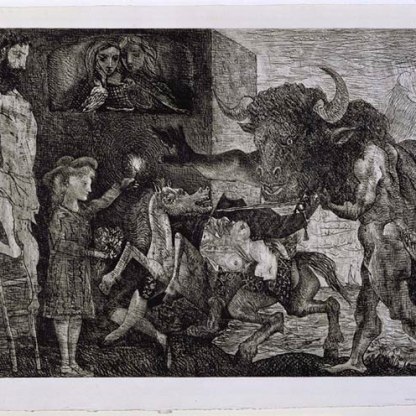

Bulls play important parts in other Greek myths, particularly those associated with the island of Crete. Herakles carries off a monstrous bull from Crete, which is then slain by Theseus on the plain of Marathon. The half-bull, half-man Minotaur is the fearsome offspring of the unnatural lust for a bull of the queen of Crete, Pasiphae. One Cretan myth held that the world rested on the back of giant bull.

In contrast to the Minotaur, the river god Achelous, another adversary of Herakles, was imagined as a bull with a man’s head.

When called upon by his son Theseus to punish Hippolytus, the sea-god Poseidon sent a monstrous bull from the sea to frighten the young man’s horses, an episode vividly captured in Rubens’ c.1611 painting in the Fitzwilliam, above [PD.8-1979].

One of the most famous sculptures of fifth century Athens was a marble cow by the great sculptor Myron. It no longer survives but is celebrated in over thirty short Greek verses, which express wonder at its naturalism: 'In vain, bull, do you rush up to this heifer, for it has no breath in it. The sculptor of cows, Myron, has deceived you.'

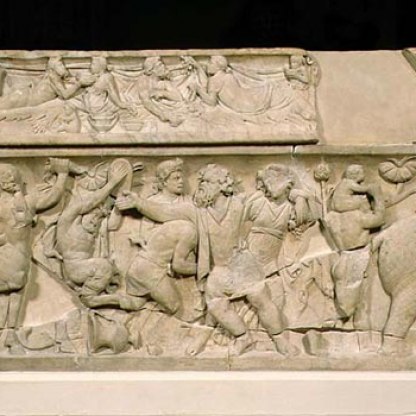

In the Bible and in Christian art, bulls and cows appear in a number of guises. In the Book of Exodus, the Israelites commit a great heresy when, having lost faith in the leadership of Moses, they build and worship a golden effigy of a calf. When Moses comes down from Mount Sinai, having received the Tablets of the Law containing the Ten Commandments from God, he is furious to discover his followers’ spiritual infidelity:

And it came to pass, as soon as he came nigh unto the camp, that he saw the calf, and the dancing: and Moses’ anger waxed hot, and he cast the tables out of his hand and brake them beneath the mount. And he took the calf which they had made, and burnt it in the fire, and ground it to powder, and strewed it upon the water, and made the children of Israel drink of it.

Exodus, 32, 19–20

Above is a painting in the Fitzwilliam [262] from c. 1630, by the Flemish painter Frans Francken II, showing the worship of the golden calf. The Israelites eat, drink and flirt at tables arranged around a pillar on which the bovine effigy stands. At the left stands an incredulous, furious Moses.

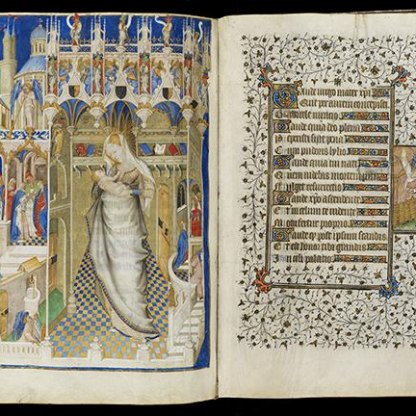

Although not mentioned in the Bible, an ox and an ass are frequently shown keeping the infant Jesus warm in the stable at his Nativity. Medieval theologians took the ox to represent the Jewish people who would be converted by the teachings of Christ. In a detail from a painting by the Florentine artist Domenico Ghirlandaio, above [M.54], we see the ox and ass behind the Virgin Mary, who prays over her newborn child.

The Evangelist Luke is often represented or accompanied by an ox. This is because the ox was a sacrificial beast and Luke’s gospel opens with Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist, performing a sacrifice. As a sacrificial animal, the ox was also, like the lamb, used to symbolise Christ in Christian writings.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…