Psalter

'Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom; teaching and admonishing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in your hearts to the Lord.' St Paul’s Letter to the Colossians, 3, 16.

A psalter is a book containing the Old Testament Psalms: songs of praise, of thanksgiving and of lament which were written in Hebrew over three thousand years ago. The word comes from the Greek psalmos, which originally described the sound of the harp.

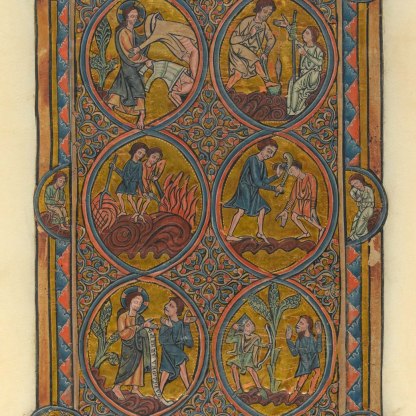

In the middle ages, the Old Testament King David was believed to have been the author of the Psalms, and he often appears in miniatures accompanying the texts. In folio 78r of this thirteenth-century psalter from Peterborough, we see David involved in his most famous act of heroism, the slaying of the giant Goliath.

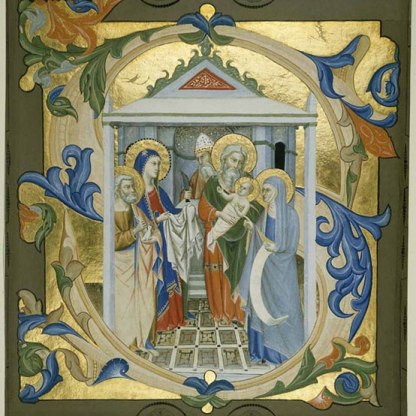

As St Paul’s words above suggest, the Jewish Psalms were embraced by Christianity early on in its history, and the Book of Psalms remains the Old Testament text most frequently used in the services and offices of the church. On a ninth-century ivory panel in the Fitzwilliam, below M.12-1904, a priest is depicted, surrounded by his choir. In an open book in his left hand, we can read the words 'Ad te levavi animam meam, deus meus' – 'unto thee, O Lord, do I lift up my soul' – the opening words of Psalm 25, which provides the text for the start of the Mass on the first Sunday in Advent.

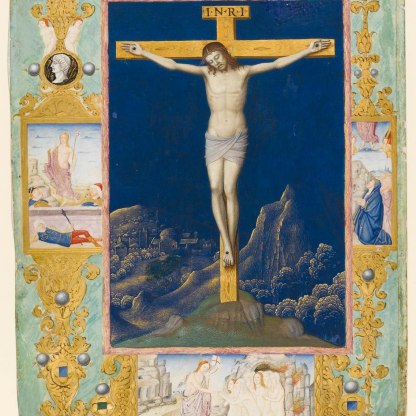

The Gospels record that Christ himself quoted the Psalms upon the cross. When at Luke 24, 46, immediately before his death, Jesus says 'Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit', he is using the words of Psalm 31, 5.

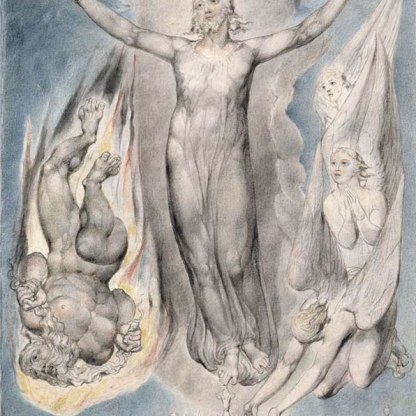

Other passages from these songs were thought to foretell the Passion of Christ. At Psalm 22, 16–18, for instance, we read '... the assembly of the wicked have enclosed me: they pierced my hands and my feet ... They part my garments among them and cast lots upon my vesture' – words which were thought to presage the Crucifixion. And it is this Christian interpretation of the Psalms, as prophecies of the life and suffering of Jesus, that justifies the subject of the full-page miniature illustrated in the margin here.

Against a gold background, a haloed Christ is crucified upon a light green cross. His eyes are closed, his wounds bleed and his body is limp – it is the moment of his death. On the right stands Mary, his mother. One hand is raised to her cheek in a gesture of grief, while the other holds a book.

Opposite her is St John the Evangelist. Like Mary, his head is inclined in sorrow as he closes his eyes and clasps his hands in prayer. On either side of the upper portions of the cross the sun and the moon appear – traditional symbols in medieval depictions of the Crucifixion. Among other things, they represent the cosmic repercussions of Christ’s death.

The sheen of the punched gold lends a remarkable visual freshness to this centuries-old image. The formal, finely balanced composition and the slender figures with their slim, elongated limbs and carefully modelled flesh, are characteristic of the very best early English Gothic painting.

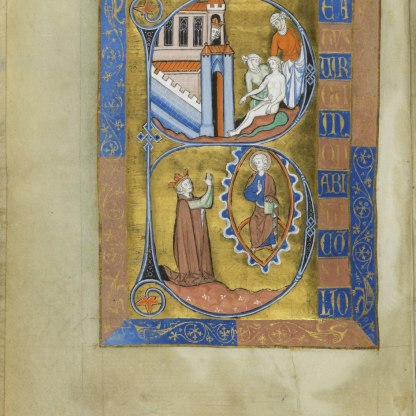

One of the most distinctive forms of decoration in a psalter is the decorated initial B usually found at the beginning of the first Psalm. Such elaborately painted letters are called 'historiated' – they literally carry a story.

On folio 12v of this Psalter there is a huge B beneath which, in smaller capitals, we read ‘-EATUS VIR,’ the Latin for 'blessed is the man', the first words of Psalm 1. In the upper circle of the letter, Christ sits in glory, directly facing the viewer. His right hand is raised in a gesture of blessing, while in his left he holds a chalice. An undulating black, white and green line at his feet suggests the heavenly realm that he inhabits.

In the lower field are two crowned women, each holding a book and a flowering sceptre. They are probably allegorical figures representing Mercy and Truth, and refer to a passage at Psalm 85, 10:

'Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed each other.'

There are comparatively few miniatures in this psalter, but what painting there is, is of exceptionally high quality. The book is thought to have been made for Robert de Lindseye, the abbot of Peterborough, who died in 1222. It is perhaps he who is represented on folio 139b, as a bishop kneeling before an altar.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Stories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…