Leaves from the Hours of Charles de Martigny

These miniatures are precious survivals from an exquisite Book of Hours. It was illuminated by the royal painter Jean Bourdichon for Charles de Martigny, a powerful bishop and courtier of Charles VIII of France.

Not surprisingly, given his royal connections, Charles de Martigny entrusted the decoration of his Book of Hours to the most favoured court painter. Jean Bourdichon, who illuminated manuscripts for the royal family and painted their portraits, included a life-like image of Charles de Martigny in his Book of Hours.

Learn more about these leaves by exploring the sections below or selecting the images on the right. Discover further details by choosing any of the images with the hotspot symbol ![]() .

.

The manuscript was illuminated by Jean Bourdichon and his workshop assistants.

These leaves belonged to a Book of Hours made c. 1485-1494 for Charles de Martigny, Bishop of Elne (1475-1494). By the 19th century, at least one of them (Marlay cutting Fr. 6) belonged to Samuel Rogers (1763-1855) and was acquired in 1856 by Thomas Miller Whitehead (1825-1897). Subsequently, all three leaves were in the possession of Charles Brinsley Marlay (1831-1912), who bequeathed them to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1912.

These leaves would have introduced the main liturgical divisions of Charles de Martigny’s Book of Hours. A portrait of the patron is incorporated in the full-page miniature of the Mass of St Gregory. The two other surviving leaves have large miniatures with arched tops and three lines of text written beneath the images. The latter also have full-borders of pink and blue acanthus sprays on gold grounds, incorporating floral motifs, birds, animals and grotesques.

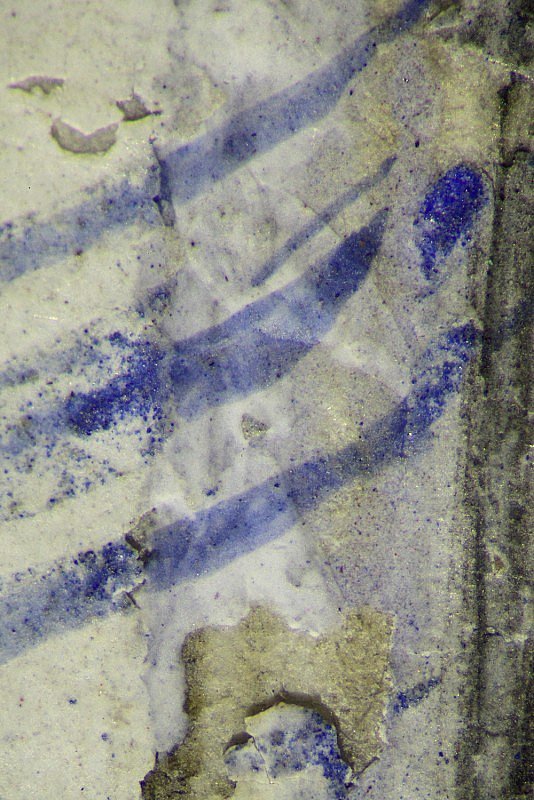

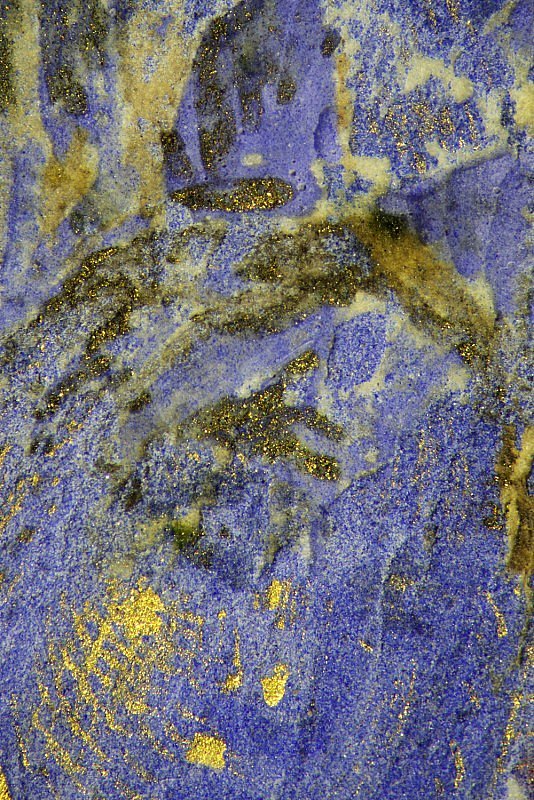

The common palette, identified in all three leaves, includes carbon black, lead white, brown earths and vermilion red. The decorated borders which frame two of the miniatures contain lead-tin yellow, malachite green, organic pinks and azurite blue, with dark blue accents painted with ultramarine. Shell gold was used extensively, and shell silver was employed to paint the clouds in the Mass of St Gregory. The latter miniature also contains some modern pigments, which bear witness to a ‘restoration’ campaign carried out during the 19th century.

The palette used in the three miniatures is not homogeneous. Some of the variations may be due to differences in subject matter and setting, i.e. the sombre tones of an outdoors night scene versus the brighter hues of a lit interior. These colour variations are reflected in the choice of different pigments.

Mass of St Gregory (Prayer recited before Mass)

According to tradition, while Pope Gregory the Great was celebrating Mass, he had a vision of the wounded Christ. Gregory’s mystical experience was widely interpreted as confirmation of the truth of the doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that during the Mass, the bread and wine are miraculously transformed into Christ’s body and blood). In this miniature, Christ looms above the altar, with blood flowing from his wounds. Dressed in gleaming white garments, two angels support his slumped figure. Clasped in the hand of the angel on the right are the three nails used to fasten his hands and feet to the cross. Surrounded by silver-lined clouds, more angels, painted in azurite over an ultramarine sky, bear additional emblems of Christ’s death and suffering (Arma Christi).

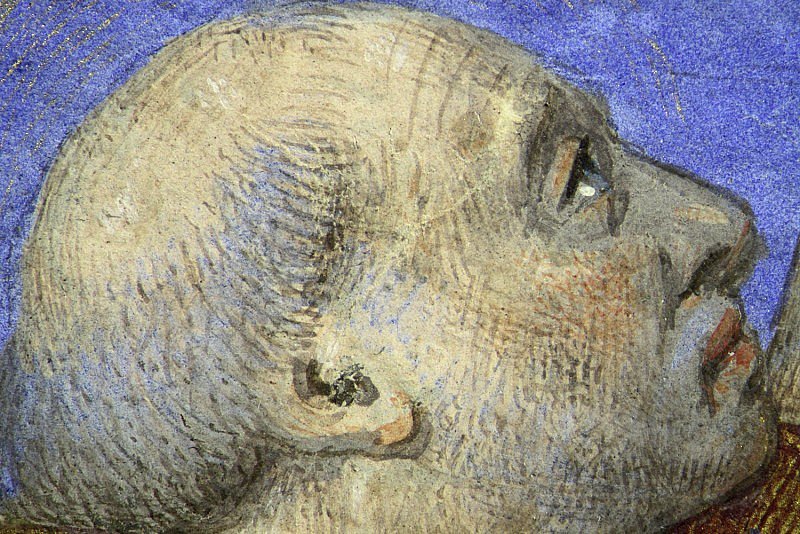

Charles de Martigny kneels near the altar, behind Pope Gregory the Great (c. 540-604) who holds the host aloft. Charles is dressed in a white liturgical garment (an alb), rather than more ostentatious vestments. The delicate execution of the figures, the individualized likeness of the patron, the red, swollen eyes of Christ’s grief-stricken attendants, and the treatment of his dead body find close parallels in other works by Jean Bourdichon.

The text of the prayer continues on the reverse, which is decorated with a one-sided, vertical border in the outer margin of pink and blue acanthus and floral sprays on a gold ground, and a bird. The text is mostly obscured by paper pasted onto the reverse.

Related content: Leaves from the Hours of Charles de Martigny

- Artists: Jean Bourdichon

- Owners: Charles de Martigny

- Texts and Images: Mass of St Gregory

- Description and Contents: Physical Description

- Description and Contents: Script and Textual Contents

- Artists' Materials: Differences in palette

- Artists' Materials: Modern interventions

- Artists' Techniques: Painting the flesh

- Artists' Techniques: Painting with gold