Leaves from the Hours of Albrecht of Brandenburg

Painted by the Flemish artist Simon Bening (1483-1561), these miniatures once formed part of a sumptuous Book of Hours made for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg (1490-1545).

Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, a wealthy aristocrat and discriminating art collector, commissioned three manuscripts, including the Book of Hours to which these miniatures belonged, from the foremost Flemish illuminator of the day. Simon Bening (1483-1561), whose career spanned six decades, was famous for deeply moving devotional images, which combine dramatic intensity with vivid narrative. These leaves reveal his ability to transform the small, flat surfaces of the pages into three-dimensional spaces of remarkable depth and complexity.

Learn more about these leaves by exploring the sections below or selecting an image on the right. Discover further details by choosing any of the images with the hotspot symbol ![]() .

.

The works of Simon Bening were admired throughout Europe, leading to commissions from wealthy merchants, aristocratic collectors and royal patrons, including Emperor Charles V and Don Fernando, the Infante of Portugal. In order to meet the high demand for his work, Bening employed assistants. Four of the Fitzwilliam’s six leaves were painted by Bening himself, while the other two involved assistants.

The opulent Book of Hours to which these six leaves belonged was made for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg (1490-1545). The leaves were in Rome by 1856 when they were acquired, along with many other miniatures already detached from the manuscript, by Frederick William Robert Stewart, IV Marquess of Londonderry (1805-1872). Five of the leaves (MSS 294a-e) then came into the possession of Rev. E.S. Dewick (1844-1917), and were purchased from his son by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1918. Later owners of the sixth leaf (MS 3-1996) include Captain C. Pitt-Rivers, Horace A. Buttery, and Phyllis Giles, Keeper of Manuscripts and Printed Books at the Fitzwilliam Museum (1947-1974), who bequeathed it to the museum in 1996.

Personal prayer books were essential to the daily devotional practices of both the clergy and lay people. In the later Middle Ages, Books of Hours became increasingly ornate, filled with numerous full-page miniatures designed to evoke empathetic responses from viewers. Before they were removed from the original manuscript, these full-page, framed miniatures would have marked major divisions in the text. Each one has an illusionistic border with strewn flowers, devotional objects or narrative scenes.

The six leaves display Simon Bening’s characteristically varied and rich palette, which includes lead white, azurite blue, indigo, lead-tin yellow, vermilion, red lead, and earth pigments ranging in hue from brown and red to yellow. The artist used organic colourants to obtain both pink and yellow hues. Natural copper sulphates, occasionally mixed with lead-tin yellow, provided a wide range of green hues, most readily observed in the leaf with the Annunciation (MS 294b). Shell gold was used extensively, from details in the miniatures and borders to highlights on the frames and the simulation of natural, divine and infernal light.

Bening employed a range of painting techniques for the modelling of draperies, the treatment of flesh tones and the simulation of light effects and atmospheric perspective.

Crucifixion

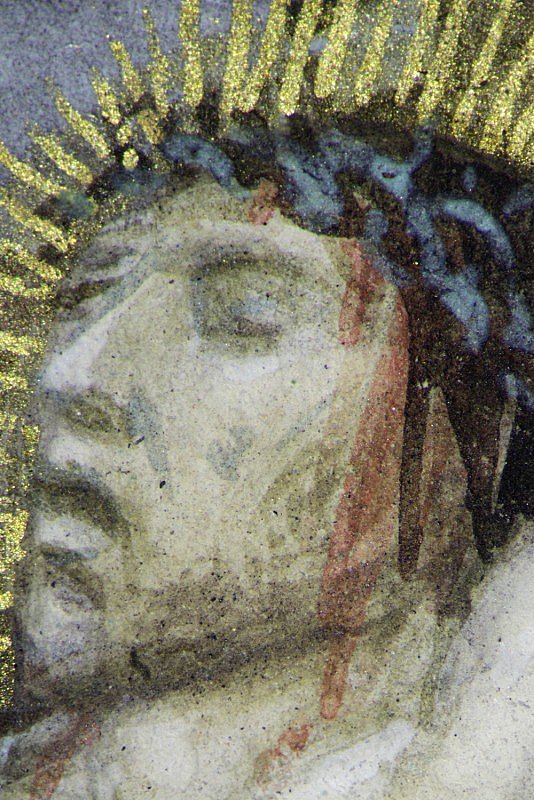

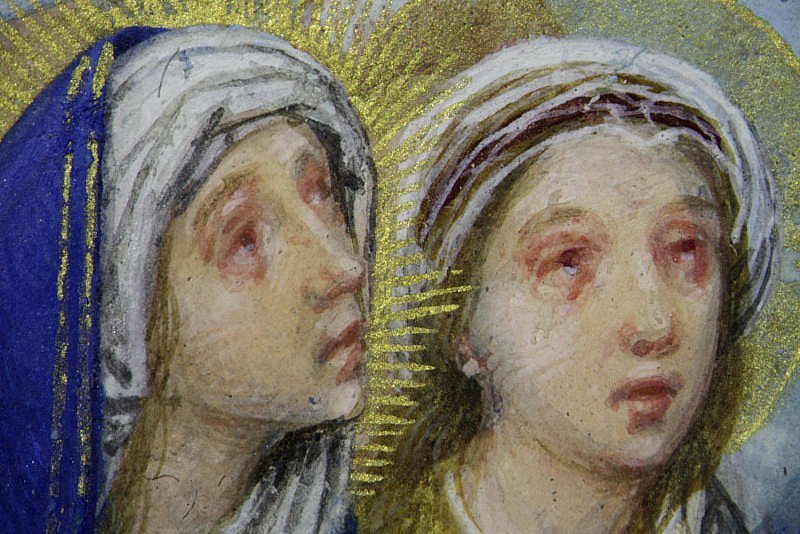

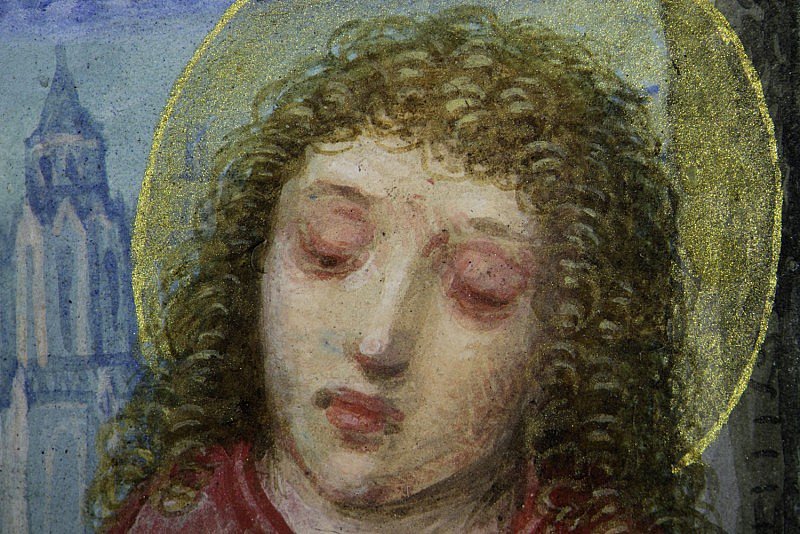

This poignant scene shows the Virgin Mary, her companion and Saint John overwhelmed by grief at the sight of Christ’s suffering. Clustered near the base of the cross they keep vigil, with their eyes red and swollen from crying. The unrepentant thief on Christ’s left, having scorned the Saviour, has turned away. The good thief, aligned with Christ, his head strenuously lifted for a final gaze at the sky, embodies the hope for salvation.

Bening intentionally varied the flesh tones of the three crucified figures. Christ, pale and chalky in appearance, was painted with lead white and modelled with brown ochre and azurite blue in the grey shadows of his body and face (hotspot 1). The thief turned away from Christ was rendered with a mixture rich in yellow and brown ochres and azurite blue, perhaps his choleric flesh colour symbolically referencing his betrayal (hotspot 2). By contrast, the good thief is painted in a similar shade to that of Christ, though with slightly more vermilion red, with indigo blue in the shadows (hotspot 3). The subtle distinction in the colours used to paint the two thieves associates one with the Saved and the other with the Damned.