Gold tooling

Artists' Techniques

The intricate designs on the haloes emulate the pioneering punchwork of early-fourteenth-century Sienese artists. Each halo in the Presentation in the Temple displays a different pattern, as does St Laurence’s halo.

The gold backgrounds are not tooled; they were all laid over a thick gesso ground and burnished to a high shine, conveying a three-dimensional impression. Such effect has unfortunately been lost in the two initials which were glued onto cardboard in the 19th century. The individual squares of thin gold leaf, which were carefully laid side by side to form these stunning backgrounds, can be identified in the elemental maps for gold obtained for each of the initials (see layer ‘elemental map Au’).

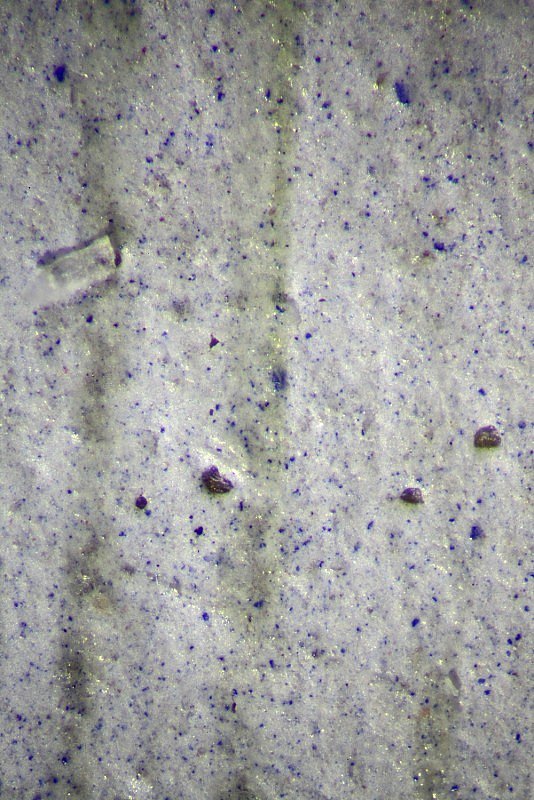

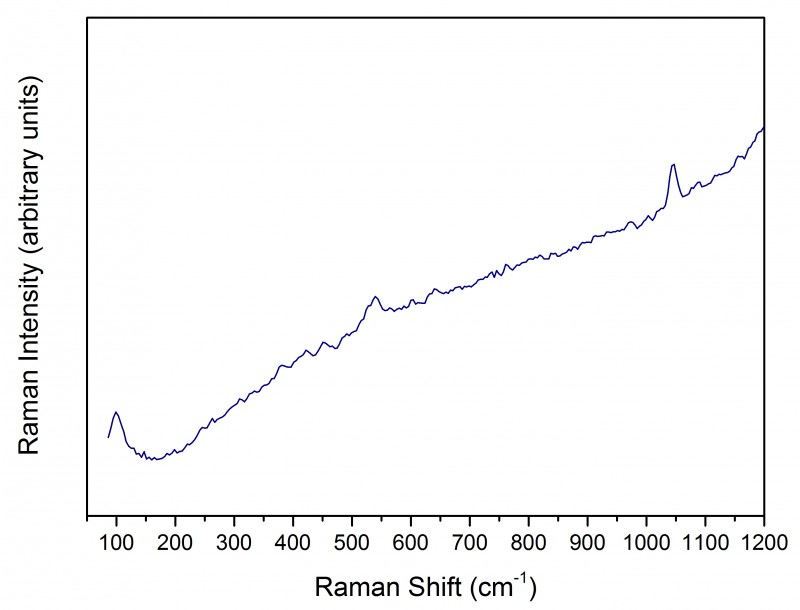

Detail of St Clement’s white robe under magnification (60x). Numerous blue particles can be seen and identified as ultramarine by a small peak at 539 cm<sup>-1</sup> in the Raman spectrum (below). The more intense peak at 1050 cmcm<sup>-1</sup> is characteristic of lead white.

St Clement

Historiated initial D from a Gradual, 1370-1375

The initial D opened the Mass for St Clement’s feast (23 November) in Corale 2, a Gradual made in 1370-1375 and illuminated by Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci. The individualised physiognomy, emulating the facial types of Simone Martini and paralleled in works by his followers, demonstrates Don Silvestro’s familiarity with Sienese painting.

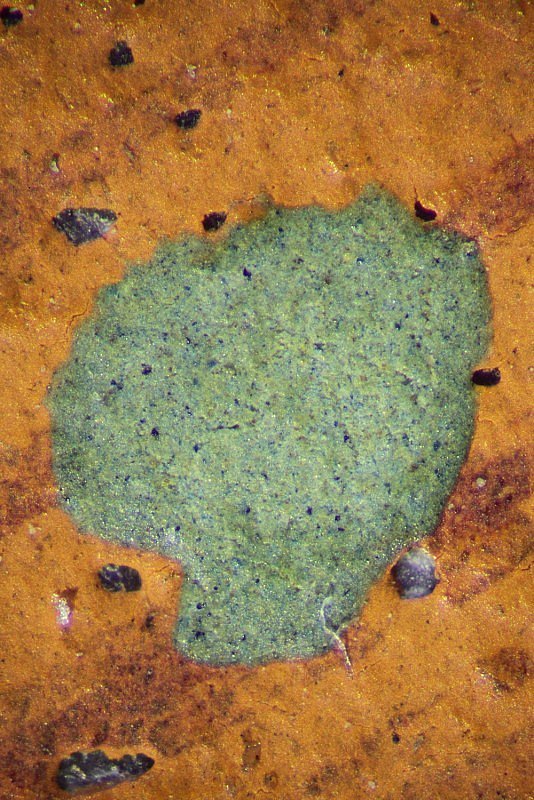

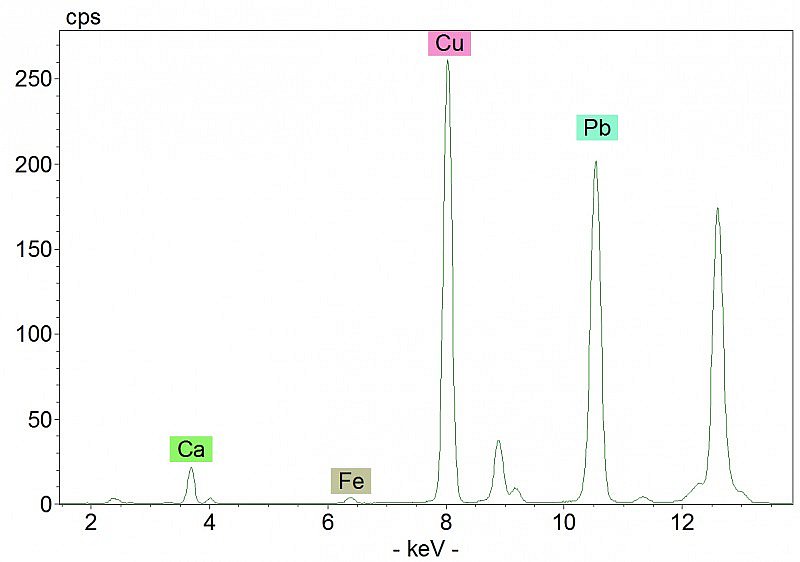

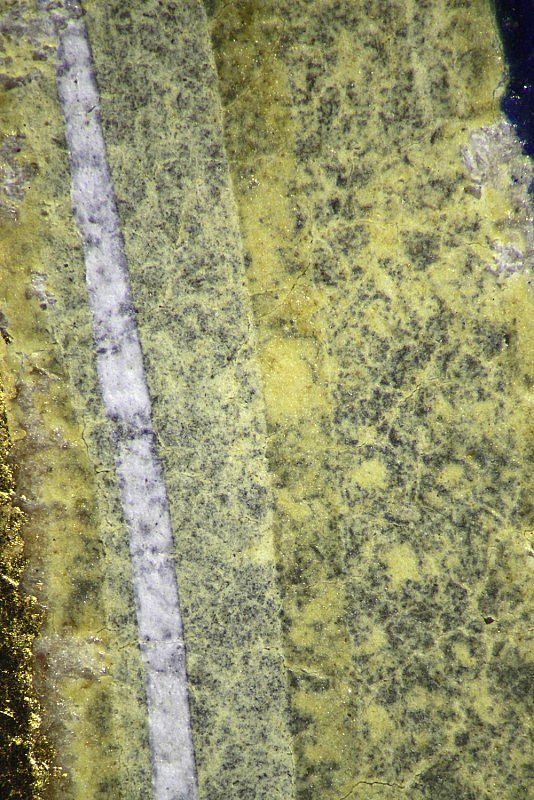

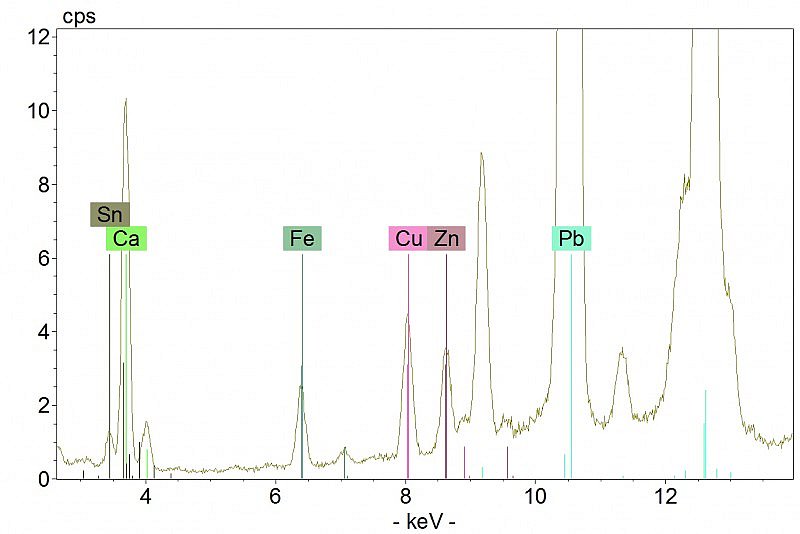

Typically Florentine, however, is the use of a mixture of blue and yellow to obtain green, while in Siena artists favoured the green copper mineral malachite. Here, azurite blue was probably mixed with a lead oxide yellow (hotspot 1). This same pigment was also used in the yellow highlights over the green leaves and in the book held by the Saint. The yellow initial, however, was painted with lead-tin yellow, as can be seen by selecting the elemental map for tin (Sn, layer ‘elemental map Sn’). The same map also shows that a small section of the blue mantle’s gilded border was painted with mosaic gold (tin sulphide), perhaps as an afterthought. Mosaic gold was also used for the small yellow dots which decorate the mantle, and for the shiny ornaments and leaf outlined in a dark red iron oxide pigment (Fe, layer ‘elemental map Fe’).

The pink leaves and the yellow initial, as well as the white highlights over the orange leaves and ornaments, have darkened significantly (hotspot 2). This is most likely linked to the presence of lead white. In the pink and yellow areas the discoloration appears to have started not on the surface but rather in the lower portion of the paint layers. If this is indeed the case, the degradation process may have been catalysed by the materials used to glue the fragment to its modern cardboard support.

Microscope images acquired in raking light provide evidence of the previous existence on the front side of the image of a brown cardboard mat, stamped with flowers and other decorative elements, similar to the one still visible around the Presentation in the Temple. The impressions left by these flowers are still visible especially along the lower edge of the fragment (hotspots 3 and 4).

Related content: Initials from Choir Books

- Artists: Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci (1339-1399)

- Texts and Images: St Clement

- Description and Contents: Physical Description

- Description and Contents: Script and Textual Contents

- Artists' Materials: Differences in palette

- Artists' Materials: Selective use of egg yolk binder

- Artists' Techniques: Gold tooling

- Artists' Techniques: Painting the flesh