Self-Portrait with Patricia Preece

There is something between you and me which must not be broken. The law does not allow me to have two wives. Yet I must and will have two. My development (as an artist) depends on my having both you and Patricia.

From an unsent letter by Stanley Spencer to Hilda Spencer, 8 September 1936.

On 24 May 1937, Stanley Spencer’s divorce from Hilda, his first wife and the mother to his two children, was finalised. Five days later he married the artist Patricia Preece, the woman who appears so exposed, so disenchanted, in this remarkable double portrait. He was now ready to put a long-cherished plan into action.

After the wedding, Patricia went to St Ives in Cornwall, accompanied by her long-time companion Dorothy Hepworth. Stanley himself remained for a few days to finish some work in Cookham, the small Berkshire town where he had been born and which he had made famous through his paintings. Within days, having enticed Hilda from London, he had successfully seduced his freshly divorced wife. He recorded his rapture at this achievement:

For the only time in my life so far, I had the joy of doing what for years I had wanted to do, namely to make love to two women at once.

Unfortunately he does not seem to have explained his domestic ambitions to the two women who were earmarked to play so vital a role in them. He was genuinely surprised when Hilda ‘seemed upset’ the next day as he announced that he was going to join his new wife in St Ives. And however much Patricia may have known of his desires beforehand, she reacted furiously when he confessed his most recent conquest to her. Although they had been lovers for several years, the marriage was never consummated, and, on returning to Cookham, Patricia moved back to her old house with Hepworth. The penitent Hilda remained in London and Stanley found himself with no real wives at all.

Was he being hopelessly naïve? Grotesquely egotistical? Both? This painting, which was probably made sometime during his extraordinary marital year, suggests a humility and self-knowledge that appears to have been lacking in his conduct.

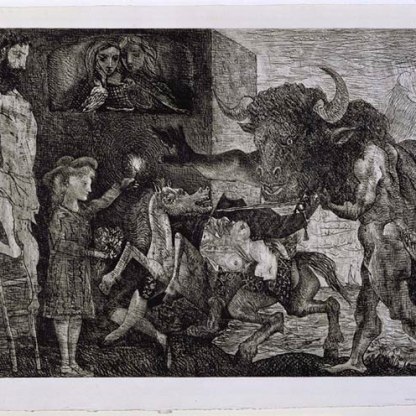

It is easy to believe that the artist who has recreated this woman’s naked body in paint was obsessed by it. Spencer himself compared his method of painting Patricia in extreme close-up to an ant crawling over the contours of her body. The creases in her neck, breasts and nipples, the minutely depicted pubic hair, the sharply protruding pelvic bone, the brilliantly observed range of skin tones: all are almost unsettlingly forthright. One has to perhaps go back to the work of the great seventeenth-century Dutch artist Rembrandt to find the female body treated in so frank and realistic a way. Left [AD.12.39-74] is a copy of his print Woman Sitting Half-Dressed beside a Stove, from 1638.

But if this suggests a profound physical intimacy, there seems to be an emotional gulf between the couple. Patricia’s head, resting uncomfortably on her hand, wears a bored, disappointed expression. Her eyes gaze dejectedly towards the bottom of the canvas, while Spencer stares directly at her, not apparently much happier than she. The sheets are crumpled and Spencer is notably red in the face, but there is little sense of fulfilment. Does the painting visualise his fears, expressed at this time, about his sexual inadequacy?

It is faintly comic that, though clearly naked himself, Spencer has kept his spectacles on, presumably the better to view the body of his beloved. One is reminded of another print by Rembrandt in the Fitzwilliam, left [AD.12.39-159], showing the Greek god Jupiter, in the form of a lecherous old satyr, leering at the reclining, naked form of the sleeping Antiope.

A major theme in Spencer’s work throughout his life was the presence of the divine in everyday things. His religious paintings all take place in contemporary settings. Christ preaches at Cookham Regatta in a series of paintings from 1955. In The Betrayal (1923), the walled garden of Fernlea, the house on Cookham High Street where the artist was born, stands in for the Garden of Gethsemane. And around 1935 he conceived the idea – never realised – of a ‘Church House', each room of which would be filled with his paintings celebrating this union of the sacred and the profane. One ‘chapel’ was to contain his intimate portraits of Patricia.

'Desire is the essence of all that is holy', Spencer once said, and he saw his love for Hilda and Patricia as somehow sacramental. Here, he kneels before the prone figure of his naked second wife like a communicant at an altar.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1963

Dating

- 1930s

- Production date: AD 1937

Maker(s)

- Spencer, Stanley Painter

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordOther highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…