Minotauromachia

'If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line, it might represent a Minotaur.'

The Spanish artist Pablo Picasso was eighty years old when he made this observation. He had lived through two world wars and a civil war in his native land. He had married three times, had many lovers and fathered four children. His was a turbulent, passionate life, best represented, he suggested, by an ancient mythological hybrid – the half-man, half-bull Minotaur, seen left on a fifth-century BCE coin from Crete [McClean 7050].

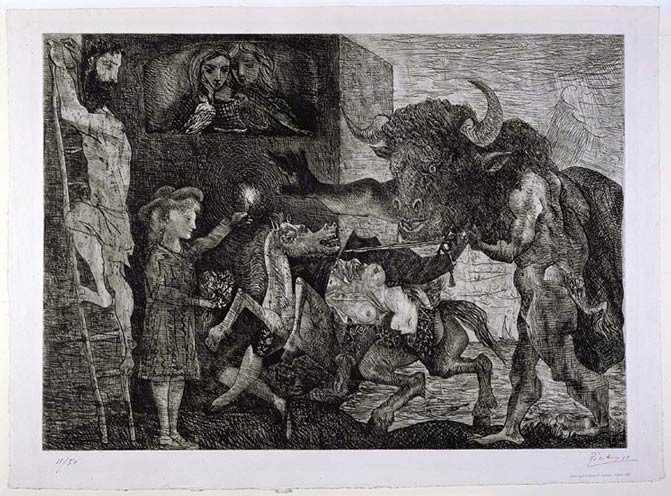

The figure of the Minotaur recurs throughout Picasso’s work, appearing first in etchings made in the 1920s. He is an ambiguous figure, in behaviour as well as form. He might appear as a participant in an orgy or as a sexually threatening monster, poised over a sleeping woman. But he might also be represented as an artist himself, or as a blind and helpless freak, led along by a small girl. He is both man and animal. He threatens women and he relies upon their help. He creates and he destroys.

This print is crammed with symbols and allusions, with references to religious art and to Picasso’s own personal mythology and experience, and, like the artist’s schizophrenic alter ego, it defies any single, rigid interpretation. Despite, or perhaps because of this, it exudes a powerful fascination.

The title means literally ‘Minotaur fight', and the central dramatic event is a confrontation between a young girl holding a candle and a bunch of flowers, and a vast, truly monstrous Minotaur. This is a superb creation by Picasso: a massive buffalo’s head with sharp, menacing horns, beady eyes and flaring nostrils, protrudes from a muscular human body.

Even its human members reflect this Minotaur's dual nature. The left arm and right leg are recognisably those of a well-developed male, but the left leg and the huge right arm that lunges forward are oversized deformations. If there is a battle going on between man and beast within this creature, then beast is winning. And there is something eerie in the young girl's calm before this hulking presence.

Above the girl, two women are visible, framed by the darkened window of a building that juts out into the sea and divides the composition in two. They look down at a pair of doves perched on the sill before them.

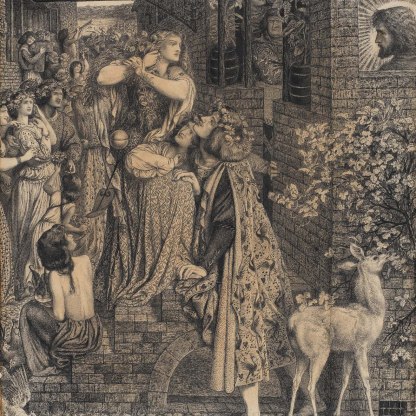

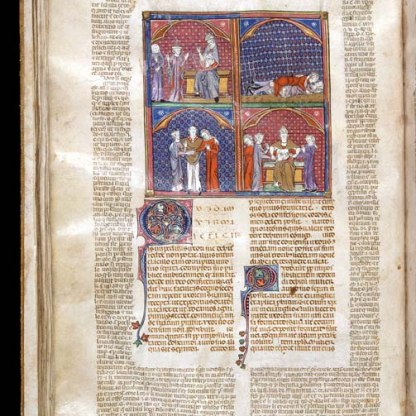

At the far left, a bearded man, wearing a loincloth ascends – or descends – a ladder. Is he fleeing the oncoming monster? His Christ-like appearance and the ladder remind one of scenes of the removal of Christ’s body from the cross, such as that from a fifteenth-century French Book of Hours [MS.62.f.134r].

Between the monster and the girl is the violent heart of the image: a rearing horse turns its agonised face towards the Minotaur, from which it seems to be running. Its belly has been gored, a wound with which Picasso would have been familiar from his visits to the bullfighting rings of Spain and southern France. Guts spill onto the earth like the contents of the cloud in the sky behind the Minotaur’s shoulder. Does the horse’s blood fertilise the earth, like the rain? Is there a suggestion of sacrifice here, of blood shed for the common good?

On the horse’s back lies a torera – a female bullfighter. Her breasts and belly are bared and her eyes are closed. In her raised right hand is a sword, the pommel of which is at the Minotaur’s neck. Some commentators have suggested that her stomach shows signs of pregnancy. Still more have recognised in her face the features of Picasso’s young lover Marie-Thérèse, who was indeed pregnant with the artist's child in 1935, while he was still married to his first wife, Olga Koklova. Picasso's domestic difficulties meant that he produced very little work that year. He scarcely painted at all, and it seems reasonable to look for some autobiographical content in this frenzied print.

Does the blood streaming from the ripped belly of the horse, upon which his pregnant mistress lies sprawled, suggest anxiety about miscarriage, or the possibility of abortion? Does the Minotaur shield his eyes from the candle held by the child because she has suddenly shed light upon his crime? Has the impending arrival of a new child alerted the man-beast, artist-Minotaur to the cruelty he has inflicted upon those around him?

Minotauromachia is the product of a troubled and brilliant imagination. It is unsettling for its violent imagery, but also for the fact that its meaning will always be just out of reach.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Given

- Dates: 1936

Dating

- 1930s

- Production date: AD 1935

Maker(s)

- Picasso, Pablo Printmaker

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

The Bee Border - Tea towel

£12.00

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…