Leda and the Swan

Whiles the proud Bird, ruffing his fethers wyde / And brushing his faire brest, did her invade, / She slept; yet twixt her eyelids closely spyde / How towards her he rusht, and smiled at his pryde. /

Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queen, 3.II.32, 1590

When Jupiter, the king of the gods, wanted to seduce Leda, a beautiful queen of Sparta, he turned himself into a swan. Pretending to flee from an eagle, he was protected by the lady and took full advantage. Leda in time laid an egg from which the lethally beautiful Helen, later known as Helen of Troy, was born. This strange coupling was a popular subject for artists from the Renaissance on.

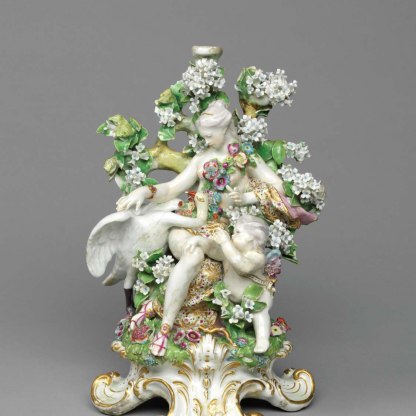

This bronze by the Florentine sculptor Massimiliano Soldani-Benzi is direct in its eroticism. A naked Cupid has laid aside his quiver to help Leda lift up her drapery and reveal her mortal loveliness, the very quality that has inflamed Jupiter. The swan, far from 'rushing' as he does in Spenser's version of the myth quoted above, sleepily rests his head and elegantly curved neck upon Leda's breasts.

Everywhere gentle curves reinforce the sensuous effect of the piece. Leda herself is extraordinarily sinuous: from her toes to her fingers, her beautiful body is a succession of smooth undulations. She gazes at her feathered lover through half-closed eyes. A contented smile shapes her pretty face, a smile that recalls the work of Leonardo da Vinci who painted a famous version of the same myth.

Indeed so languorous is the overall effect that one wonders whether Soldani has not represented the aftermath of the divine lovemaking. There is none of the aggression or blatant phallic imagery that one sometimes finds in treatments of the subject. All Soldani's brilliantly realised textures suggest softness: the flesh of Cupid and Leda, the plumages of the swan and Cupid, the little love-god's long hair, the sheet between Leda's legs. The only slightly discordant detail, not visible when one views the statue from the front, is the bird's claw resting upon the flesh of Leda's thigh.

Her half-closed eyes, her effortless smile, the arm draped casually but intimately around the back of the swan, the suggestion of the swan's own drowsiness: is one supposed to infer a sense of blissful exhaustion? Has the drapery beneath Leda been ruffled by the energy of Jupiter's lust?

What cannot be denied is the sculptor's technical brilliance. The smooth finish of the metal is stunning. Soldani was the leading European bronze-caster of his day and worked chiefly for Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici, the last of the great Medici art patrons in Florence. A companion piece to Leda and the Swan, showing Jupiter again, this time as an eagle seducing the beautiful shepherd Ganymede, is also in the Fitzwilliam M.59-1984.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Figure group. Copper alloy, probably bronze. Cast, and chased. Jupiter is disguised as a swan, and is clambering up a rocky bank to Leda, whose left arm is wrapped around the swan's body. Jupiter is assisted by Cupid, who removes Leda's draperies.

(with M.59-1984) Purchased directly from Massimilano Soldani-Benzi by Giovan Gualberto Guicciardini, Palazzo Valori (or dei 'Visacci'), Florence, 25 June 1717 (150 scudi); March 1729 by inheritance, Carlo Rinuccini (husband of Vittoria Teresa Guicciardini, daughter of the late Giovan Gualberto), Palazzo Rinuccini, Florence; 19th century, by inheritance, Prince Ludovico Trivulzio, Milan; The Luccardi Collection, Milan; Zürich art market, where purchased by John Winter; Given by John Winter, Esq. in memory of his father, Carl Winter, Director of the Fitzwilliam (1946-1966), 1984.

Legal notes

Given by John Winter, Esq. in memory of his father Carl Winter, Director of the Fitzwilliam (1946-1966)

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Given

- Dates: 1984

Dating

A pair with Ganymede and the Eagle, M.59-1984

Maker(s)

- Soldani-Benzi, Massimiliano Sculptor

Note

A pair with Ganymede and the Eagle, M.59-1984

Place(s) associated

- Florence

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…