Wine Jug

'A dullard is he who does not lend his tongue to sing of Herakles ...'

Pindar, Pythian Ode 9, 87.

Herakles, son of the supreme Greek god Zeus by a mortal mother, was the Greek hero par excellence of the Archaic Period. This is the name given to the years between c.700 BCE and c.480 BCE, when city states, ruled by a king (Greek tyrannos) or an aristocratic minority, emerged as the main political units in Greece. The rulers of these cities often legitimised their position by reference to the legendary past, claiming descent from, or connections with, mythical heroes. There were nearly forty cities in the Greek world called Herakleia which claimed Herakles as their founder.

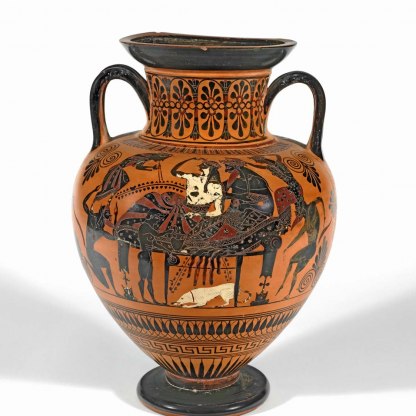

On this jug we see the hero vanquishing the Nemean lion, the first of his legendary twelve labours. He was sent by King Eurystheus, to whom he was in bondage, to kill this ferocious animal who had been ravaging the lands around Nemea in the Peloponnese. The lion was impervious to weapons, and Herakles was forced to wrestle and throttle it with his bare hands. Using one of its own claws to remove the impenetrable pelt, he wore the lion’s skin for the rest of his life, a protection from weapons and a trophy of his first great deed. In art the hero is always recognisable by the lionskin on his back.

Herakles has here hung his redundant weapons – his quiver, bow and club – from the branches of an olive tree that provides a backdrop to the fight. And like a true Athenian athlete, he has stripped naked. His cloak hangs nearby.

Locked in a classic wrestling grip with his adversary, this Herakles is a real giant. If he were to stand up, his thick thighs would reach the neck of the goddess Athena who stands nearby. Simple incisions mark the muscles of his belly, thighs, calves and arms. With his red beard and bulging eye the ‘lion-hearted’ hero resembles the beast that he grapples. The bitter snarl on the animal’s face as it is thrust into the dirt tells us which way the fight is going.

Athena’s flesh is picked out in white, as was the custom for women on Athenian black-figure pottery, but she is otherwise shown as a formidable warrior. She wears a helmet with a tall plume, and around her body the aegis – the protective goatskin tassled with snakes' heads that she received from her father, Zeus. She stretches a muscular arm protectively over Herakles.

The direct association of Herakles with this goddess, the patron of the city of Athens, is perhaps enough to explain his frequent appearance in the city’s art at this period. It has been suggested that the hero was particularly promoted in Athens towards the end of the sixth century by the tyrant Peisistratos and his sons. But he continues to appear, as here, after the expulsion of the last Athenian tyrant in 510 BCE.

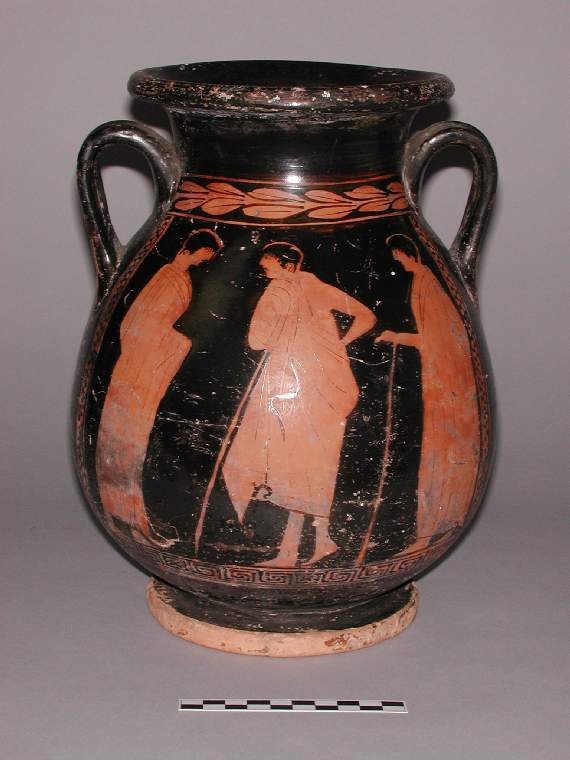

The archaic Herakles, ‘the warder-off of evil', was essentially a loner, a man who got by on sheer courage and brute strength. When democracy was firmly established in Athens in the first few years of the fifth century BCE, another more social and specifically Athenian hero would become popular – Theseus who, like Herakles, rid Greece of monsters. We see him on a vase in the Fitzwilliam, below GR.13.1917, from c. 470 BCE, attacking the brigand Sinis and making safe the roads around Athens.

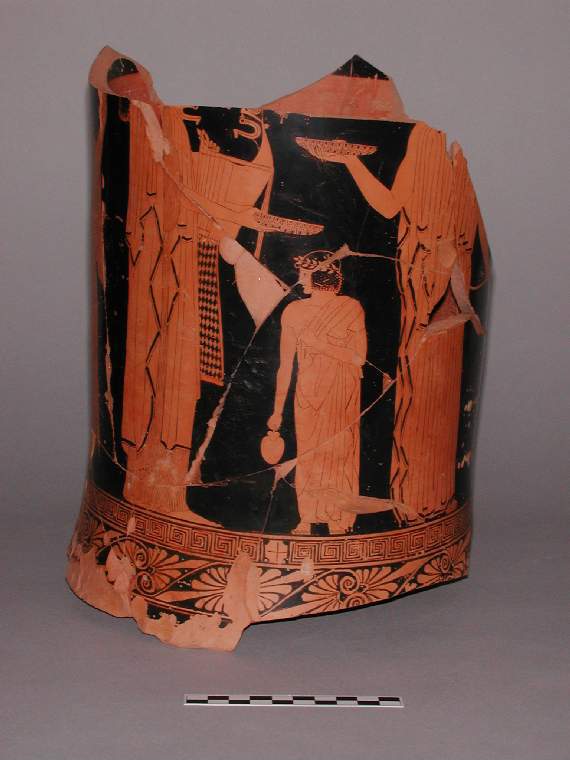

The vessel here is called an oinochoe, a wine jug. One can be seen on a fragment of a red-figure vase stand in the Fitzwilliam, below GR.P.13. It is held by a young boy, possibly Ganymede, whom Zeus abducted and employed as his personal wine waiter.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Oinochoe, Athena, Herakles and the Nemean lion

Legal notes

The Ricketts and Shannon Collection. Bequeathed by Charles Shannon, 1937

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1937

Dating

black-figured

- Archaic

- Production date: 500 BC

Place(s) associated

- Athens

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…